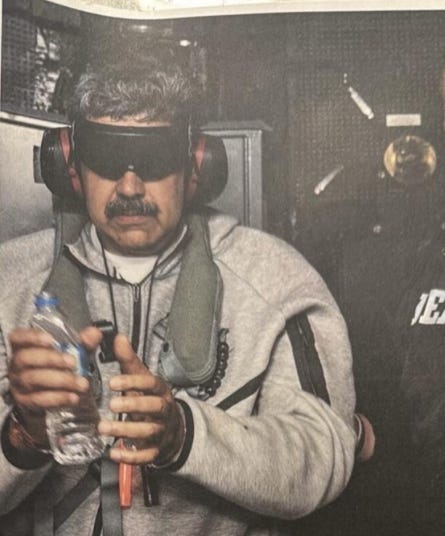

Caracas by night

Heavy-sour structural repricing

On January 3, 2026, Delta Force operators extracted Nicolás Maduro from Caracas in what Washington officially framed as a narco-state takedown but what markets immediately parsed as a geopolitical reset for Venezuela’s oil architecture. The operation’s surgical precision—targeting military installations while leaving PDVSA’s critical infrastructure (upgraders, pipelines, terminals) conspicuously intact—signals a Washington playbook far more concerned with restoring flow than with punishment. For energy professionals accustomed to parsing geopolitical signals through the lens of physical supply, this distinction matters profoundly. The next 18–24 months will likely redefine the calculus of heavy-sour crude pricing, diluent dependency, and refinery economics across the Atlantic Basin in ways that cut against conventional wisdom about supply disruptions.

Throughout late 2025, Washington executed a grinding blockade campaign targeting Venezuela’s oil sector with surgical effectiveness. U.S. authorities interdicted at least seven tankers collectively laden with 12.4 million barrels of crude and diluents, forcing abrupt diversions that created immediate bottlenecks at the José export terminal and upgrader facilities. The consequences were swift and brutal: storage tanks rapidly filled to capacity, forcing PDVSA to implement production throttling across key Orinoco fields, ultimately delivering a devastating 25% output reduction and pushing national production below the 1 million bpd mark by November 2025. This wasn’t just a headline disruption; it was a premeditated squeezing of the very logistics arteries that allow Venezuelan heavy crude to reach international markets—a demonstration that sanctions enforcement had evolved from indirect administrative measures into direct physical intervention.

The diluent bottleneck proved particularly consequential. Venezuelan extra-heavy Orinoco crude, with its stubborn low API gravity (8°–10°, occasionally dipping to 4° in some blocks) and punishing sulfur content (3–4% or higher) combined with elevated vanadium and nickel levels, cannot physically flow through pipelines without massive volumes of lighter hydrocarbons—naphtha or condensate—to reduce viscosity. With U.S. sources cut off by January 2023 and Iran offline after 2023, Venezuela had pivoted to Russian naphtha by mid-2025, accumulating diluent stocks sufficient for several months of operations. Yet the U.S. blockade directly targeted this lifeline: sanctioned tankers carrying Russian naphtha began executing U-turns mid-voyage, with records showing at least one 32,000-metric-ton cargo diverted to Europe rather than risk seizure off the Caribbean. Kpler data confirms that continued access to naphtha remains “key” to operations at the José Terminal, located 250 kilometers from Caracas—a six-week import horizon means that sustained diluent shortages would become visible in upstream Orinoco production almost immediately. This technical vulnerability, more than any headline about military deployments, is what truly terrifies PDVSA planners: losing diluent access doesn’t require occupying the capital; it merely requires intercepting tanker traffic.