Cold War "Greeks"

How Beta-Squared Gamma Exposes Your Hidden Exposures

How do we properly account for our exposure to market moves when we’re holding positions across multiple underlyings? More specifically, how do we measure and manage the dynamics of delta and gamma when each underlying responds differently to market movements?

Let’s start where every options trader must start: delta. Delta is the most fundamental Greek in our arsenal. It represents the rate of change in an option’s value with respect to changes in the underlying price. In practical terms, delta answers a simple question: if the underlying moves by one dollar, how much will my position change?

This is model-free mathematics. We don’t need Black-Scholes or any particular pricing model here. We’re simply working with the basic principle that option values respond to underlying price movements, and delta quantifies that responsiveness.

For those new to thinking about deltas, a few key patterns matter. Long calls have positive deltas; long puts have negative deltas. Short options carry the negative of whatever Greeks the long options would carry. At-the-money options typically have deltas around ±50. Deep in-the-money options approach ±100, while deep out-of-the-money options approach zero.

Now here’s where a critical insight emerges: delta is only constant in one scenario—when you’re holding actual shares or synthetic shares (like a long call paired with a short put). In every other case, delta itself changes when the underlying price changes. This changing delta is our next protagonist: gamma.

Why We Can’t Simply Add Deltas

If we operated only in single-underlying portfolios, delta would be straightforward. We’d simply sum all our deltas and have a number representing our directional exposure. Done. But real portfolios span multiple underlyings—multiple stocks, multiple sectors, multiple asset classes.

The problem emerges immediately: we can’t directly sum deltas across different underlyings. Why? Because each delta has the underlying’s price change in its denominator. When we’re trying to aggregate exposure across Apple, Microsoft, and Nvidia, we’re fundamentally trying to add fractions with different denominators—a forbidden operation that would have earned us corrections in elementary school, and for good mathematical reasons.

This problem cascades when we move beyond delta to gamma. Gamma is the second derivative of position value with respect to the underlying price—the rate of change of delta itself. In mathematical terms, it contains the underlying’s price change squared in its denominator, making direct summation across underlyings even more problematic.

Long options always have positive gamma; short options always have negative gamma. And here’s something many traders find counterintuitive: gamma is highest near the money, regardless of whether we’re dealing with calls or puts. More importantly, positive theta (time decay working in your favor) correlates strongly with negative gamma. For premium sellers—those who profit from theta decay—negative gamma is an inevitable feature of the trade structure.

The Key: Beta as the Universal Denominator

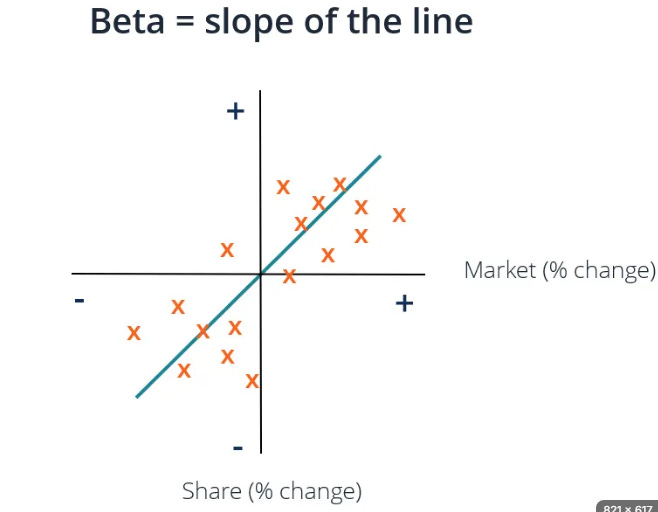

The elegant solution to this problem is beta. Beta represents the correlation between an underlying and the broader market, weighted by volatility. In practical terms, beta is the slope of the line of best fit when you plot the returns of an underlying against the returns of the market (typically measured by the S&P 500).

This slope tells us something crucial: if the market moves by one dollar, how much should we expect this particular underlying to move? An underlying with beta of 1.2 should move 1.2 times as much as the market. An underlying with beta of 0.7 should move 0.7 times as much. Beta, therefore, becomes our translator—the device that converts market movements into underlying-specific movements.

Once we have this translation tool, we can begin to solve our aggregation problem. We can transform our deltas, which have “change in underlying” in the denominator, into beta-weighted deltas, which have “change in market” in the denominator. Suddenly, they all speak the same language. We can add them together.

Beta-Weighted Deltas: The Standard Approach

Beta-weighted delta is simply delta multiplied by beta. It’s elegant in its simplicity. By multiplying each position’s delta by its underlying’s beta, we’re asking: given that the market moves by one dollar, how much will this specific position change?

This transformed metric is the standard gauge for portfolio exposure to market movements. Most trading platforms display this metric prominently—your total portfolio beta-weighted delta sits in a corner, often in the upper right of the interface, constantly updating as positions shift and markets move.

The beauty of beta-weighted delta is that it’s additive across underlyings. Because every position’s metric now shares the same denominator—market movement—we can freely sum them across Apple and Microsoft and Nvidia and all the rest. We arrive at a total portfolio number representing your systemic exposure to market movements, using the terminology of capital asset pricing models.

Many traders deliberately target beta-weighted delta neutrality. If you don’t have a strong directional conviction about the broader market—if you’re neither a bear nor a bull—maintaining near-zero total beta-weighted delta allows you to profit without requiring directional correctness. You’re free to express trades on the basis of volatility, relative value, earnings catalysts, or any number of other factors, without being implicitly short or long the entire market.

The Wrinkle: Delta Isn’t Static, So Neither Is Beta-Weighted Delta

But here’s where things get more complex, and where the real problem I want to discuss emerges. Beta-weighted delta is only stable if the position truly behaves like shares or synthetic shares. Since we’re trading options, and since options have gamma, deltas change. A lot.

Consider a simple scenario: you’ve achieved delta neutrality in a particular underlying, and you’ve achieved beta-weighted delta neutrality across your entire portfolio. Your platform shows green. Everything balances. You feel good about the position.

Then the market moves. A dollar move in the S&P 500.

Your underlying is expected to move approximately its beta amount—let’s say 1.2 dollars, given a 1.0 dollar market move. Your delta, however, will respond to that 1.2 dollar move in the underlying. And because you have gamma—almost certainly some mix of positive and negative gamma across your positions—your position value will change by more than your delta alone predicted.

More importantly, your total portfolio beta-weighted delta will change. The metric you relied upon for your total portfolio exposure is now out of sync. Your delta wasn’t as neutral as you thought. Your beta-weighted delta wasn’t as neutral as the platform suggested.

This is the practical problem that motivated my thinking on this topic. When the market moves, what happens to your total beta-weighted delta? And can we predict or approximate that change?

Introducing Beta-Squared Gamma: The Missing Piece

The answer lies in gamma, but not in the way most traders think about gamma. Instead of trying to estimate total gamma exposure using theta (the correlate but imperfect proxy), we can use beta directly. Specifically, we can use beta squared.

Here’s the mathematical intuition: gamma is the second derivative of position value with respect to underlying price. The denominator contains the underlying’s price change squared. When we want to convert this to a market-basis denominator (market change squared), we need to account for how much the underlying moves for a given market movement. That’s beta. And because we’re dealing with squared terms, we need beta squared.

This gives us beta-squared gamma: a new metric that lets us predict how our total beta-weighted delta will change when the market moves.

If the market moves by one dollar, and you have a total portfolio beta-squared gamma of 50, then your total beta-weighted delta will change by approximately 50. Your delta exposure increases or decreases by 50 shares-equivalent of sensitivity to market moves. This is tremendously useful information. It tells you not just where you are, but where you’re going as markets move.

Let me walk through this more formally, as the mathematics clarifies why this works.

Start with a position in a single underlying. The position value, V, depends on the underlying price, S:

Your delta is dV/dS—straightforward.

Your gamma is d²V/dS², the second derivative.

Now introduce beta. The market index is I.

The underlying tracks according to: approximately, dS ≈ β × dI.

Your beta-weighted delta is β × dV/dS. This tells you how your position value changes for a market move.

Now, what happens to your beta-weighted delta when the market moves? You take the derivative with respect to market movements.

This is where gamma enters. Since dV/dS depends on S, and S depends on I through beta, we get:

d(β × dV/dS)/dI = β × d²V/dS² × dS/dI = β × d²V/dS² × β = β² × d²V/dS²

In other words: the change in your beta-weighted delta, for a market move, equals beta squared times gamma.

This is why beta-squared gamma matters. It’s not an arbitrary mathematical construction—it’s the natural emergence of how portfolio Greeks transform when we shift from underlying-basis to market-basis thinking.

Multiple Underlyings

In a real portfolio, you hold positions across multiple underlyings. Each underlying has its own delta and gamma. Each has its own beta.

Your total beta-weighted delta is the sum of all individual beta-weighted deltas:

Σ(βi × Δi).

Your total beta-squared gamma is the sum of all individual beta-squared gammas: Σ(βi² × γi).

These two numbers tell you something powerful: where you are on market directional exposure, and where you’ll move when the market does.

If your total beta-weighted delta is 250 and your total beta-squared gamma is 100, then you’re currently long 250 shares-equivalent of market exposure. When the market moves up by one dollar, your beta-weighted delta becomes approximately 350 (gaining 100 from gamma). When the market moves down by one dollar, your beta-weighted delta becomes approximately 150 (losing 100 from gamma).

This dynamic is crucial for understanding your portfolio behavior. Premium sellers typically run negative gamma portfolios. As the market moves away from them, their delta becomes increasingly negative. Their hedge deteriorates precisely when they need it most. This is the volatility surface’s tax on short premium.

Conversely, long premium traders run positive gamma portfolios. As the market moves, their delta increases in the direction of the move. Their position becomes increasingly long in a rising market and increasingly short in a falling market. They benefit from large moves, which is part of what they paid for in premium.

This framework matters for several practical reasons.

First, it allows you to set expectations. Many traders stare at their platform’s beta-weighted delta number expecting it to remain stable through the day. It won’t, unless you have precisely zero gamma. Understanding beta-squared gamma lets you predict which direction your delta will drift, and by how much, for a given market move.

Second, it helps you identify hidden exposures. You might have deliberately constructed a portfolio you believe is delta-neutral. Your platform confirms it: beta-weighted delta is near zero. But if you have substantial beta-squared gamma, your neutrality is an illusion. It’s a snapshot of one point in price space. Move the market, and that illusion dissolves. Understanding this difference between static neutrality and dynamic neutrality changes how you construct and monitor positions.

Third, it informs hedging decisions. Suppose you want to achieve not just delta neutrality, but genuine protection against delta drift. You need to monitor and potentially hedge beta-squared gamma, not just delta. Many traders accidentally run significant uncompensated gamma risk without realizing it—because they were watching the wrong metric.

Fourth, it connects options portfolio management to market-wide capital asset pricing models. Your beta-weighted delta is your systematic risk in CAPM terms. Your beta-squared gamma represents your exposure to changes in systematic risk. Managing both, rather than just managing delta, aligns your options portfolio with broader portfolio theory.

The Practical Limit: When Beta Breaks Down

Before we conclude, I should note the assumptions underlying this framework. Beta is a useful approximation, but it’s not perfect. Beta is calculated using historical returns, and future returns may differ materially. Sector rotations, market dislocations, changes in correlation structures—all of these can cause beta to shift.

During extreme market stress, correlations tend to converge toward one. Beta becomes less meaningful. The relationship between underlying and market becomes less stable. Your beta-weighted delta and beta-squared gamma, while still mathematically useful, become less predictive during such environments.

Additionally, beta is derived from returns data and is typically calculated using daily or weekly observations. Intraday dynamics, overnight gaps, and microstructure effects can all violate the assumptions underlying the beta framework.

That said, for typical market conditions and typical portfolio monitoring, this framework works remarkably well. It’s robust enough to be useful for most traders most of the time.

Building the Framework Into Your Process

How should you apply this practically?

If your platform doesn’t display beta-squared gamma explicitly, you can construct it. For each position, calculate the Greek gamma. Look up the beta for that underlying. Multiply gamma by beta squared. Sum across all positions.

Make this a regular part of your monitoring routine, alongside your total beta-weighted delta. Track how it evolves over time. Start to develop intuition for what levels of beta-squared gamma feel right for your portfolio risk tolerance and your anticipated market environment.

When you’re considering new trades, think not just about their delta contribution, but about their beta-squared gamma contribution. A trade that looks delta-neutral might meaningfully shift your overall beta-squared gamma. That shift might be exactly what you want—or it might be an unintended exposure that deserves reconsideration.

Over time, this framework becomes part of how you think about portfolio construction. You stop seeing your portfolio as a collection of positions in individual underlyings. You start seeing it as a system with market-level dynamics. Your position in Apple, Microsoft, and Nvidia aren’t independent—they’re parts of a coherent portfolio with a single beta-weighted delta and a single beta-squared gamma that determine how that portfolio will respond when the market moves.

Conclusion

Spring brings the opportunity to refresh our thinking, to reconsider problems we thought we’d solved, and to build better frameworks. The problem of aggregating Greek exposure across multiple underlyings is fundamental to portfolio management, yet it’s often solved only partially—via beta-weighted deltas, without full attention to how those deltas will drift due to gamma.

By introducing beta-squared gamma alongside beta-weighted delta, we create a more complete picture of portfolio behavior. We understand not just where we are in directional exposure, but how we’ll move when markets move. We identify hidden volatility exposures. We connect options portfolio management to broader capital asset pricing frameworks. We build better risk management processes.

The mathematics here is straightforward once you see it. The practical applications are substantial. I encourage you to implement this framework in your own portfolio monitoring. Track your total beta-weighted delta and your total beta-squared gamma. Watch how they interact as markets move. Develop intuition for what these numbers mean for your specific trading approach and risk tolerance.

In doing so, you’ll have a richer understanding of your portfolio’s behavior—not as a collection of Greeks in isolation, but as an integrated system responding to market movements in predictable, quantifiable ways. And that understanding, I believe, leads to better risk management, better decision-making, and ultimately better results.

The Greeks have always offered this kind of insight. We just needed to arrange them in the right way.